Mary Beth Meehan on How a Single Photo Can Spark New Conversations

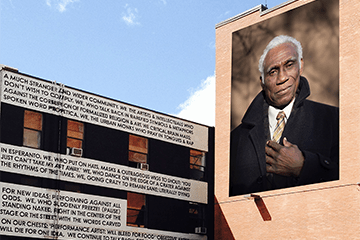

Mary Beth Meehan is a public art activist who brings important conversations to light through photography.

The Visual Arts Department at RWU welcomed Mary Beth Meehan to campus on Wednesday, March 30. Meehan is an independent photographer, writer and editor whose work has been featured in The New York Times and other publications as well as in internationally prestigious collections. She describes herself as a public art activist, someone who uses art as representational justice that allows others to see across race, gender and religion by sparking conversations about who and what is seen, and by whom. In her lecture, she explained the path of her career and the way she came to understand exactly how an image can spark a new conversation.

Meehan was born in Brockton, Massachusetts, a city that was 80% white but had many European immigrants, some of whom were her family. She went to school for English literature and art and spent many years working in journalism. However, in more recent years, racism has bubbled up in the Brockton community as more immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean move in. Though she now lives in Providence, when Meehan went back to visit her family she experienced the tension in the community in full force. This tension prompted her to take her camera and years of journalism out into the community and begin interviewing and photographing people, something that allowed her to meet individuals who hailed from all over the world.

“People want to tell you what their lives are like, if you care,” Meehan said.

Her first photography installation was put up outside her parents’ house and featured many people from the Brockton community. This public installation prompted many of those featured in her photos to show up and start having conversations with each other and her family, all thanks to a situation that they otherwise never would have been a part of. It was here that Meehan got the idea that the point of her work was to get people to see things differently.

As she went on to explain, it was following this first installation that she displayed her work in downtown Brockton as part of her “City of Champions” series. This was when her work first started getting widespread attention. Volunteers started to give walking tours of Meehan’s pictures, and one woman even went around and interviewed people about what they thought the photos meant. When one observer got very vocally upset about the pictures, Meehan was able to converse with her about why, that was when she realized just how powerful an image could be.

“You don’t know what happens when you pass by a human, either,” Meehan explained she had said to the person, who had complained about a picture of a woman in torn jeans and a tank top. “I want you to think about that.”

From there, she continued, her work slowly began to gather more attention. Her next installation, “SeenUnseen,” was put up in Providence, where one of the photos was inaugurated by the mayor. She was also commissioned by the RISD Museum to create a piece on Islam, which was accompanied by a public talk. Though she’s not Islamic herself, as she said, “the picture became a backdrop for a conversation about Islam.” It managed to get people from all different groups to have conversations together.

However, her most impactful work came about in Newnan, Georgia. As someone who grew up in New England, she explained, her work here became about grappling with her own stereotypes of the South. She visited and revisited Newnan over the course of two years, conducting interviews and witnessing moments that illustrated the community’s identity. However, when her installation “Seeing Newnan,” which featured less-seen members of Newnan’s community, was put on display, it received very vocal online backlash from members of the community. These people even went so far as to complain about and harass Meehan herself. However, the community as a whole fought back against these outliers, showing that the group did not represent everyone’s views.

“People aren’t rude,” Meehan said after her presentation concluded. “They’re amazing, like heart-to-heart. This stuff isn’t about me. I’m just the lightning rod; the communities and people come out and do the rest.”

For more information on Meehan’s work, you can visit her website at https://www.marybethmeehan.com/.