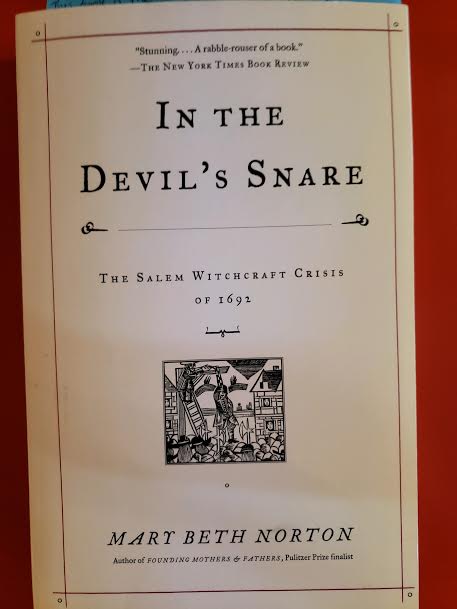

Book Review: “In The Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692”

Spencer Wright / The Hawks’ Herald

If you’re looking for a history book on the Salem witchcraft crisis, Norton’s book is a must read.

The book “In The Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692” by Mary Beth Norton is a history book that aims to cut through the suppositions about the Salem witch trials and instead look at the hard facts and links that can be drawn and observed between all the accusations and trials. The book also includes informative graphs to show the rising number of witchcraft accusations that occurred as the trials progressed.

The theme and thesis of this book is to broaden readers’ perspectives from the narrow mindset of Salem to the overall connecting themes between Salem and the larger colonial New England world. Norton makes sure readers know the histories of King William’s War, King Philip’s War and the Salem witchcraft crisis are linked in many ways. The Salem witchcraft crisis was not an isolated incident that existed in its own sphere, but rather part of a much larger narrative which this book acknowledges.

This book is also about the perspectives of the people who were affected by the witchcraft trials and gives an overview of the crisis as people in Essex County experienced it in 1692. This point is a key takeaway from this book since many histories of the Salem witch trials place emphasis on the events rather than the people impacted in the situation.

Norton, in dispelling and sifting through countless earlier works on the Salem witchcraft trials, points out that even the name is not entirely accurate. She writes on page eight that the accused “came from twenty-two different places, fifteen of those in Essex County. Although the crisis began in Salem Village and the trials took place in Salem Town, a plurality of the accused (more than 40) lived in Andover. Thus the term Salem Witchcraft Crisis is a misnomer; Essex County Witchcraft Crisis would be more accurate.” Just by changing the name to more accurately reflect the event, Norton causes readers to broaden their views and realize this was not an event contained within the limits of Salem, but rather one that had far-reaching effects.

Norton also notes that when looking at the people involved in the events, one realizes that young women and girls were considered credible accusers and taken very seriously. To a modern reader, this might not sound at all out of place, but in the 1600s, this was wildly outside social norms. Norton spoke about how girls and servants of lower ranks were supposed to be seen and not heard, in accordance with social norms. They also completed whatever tasks were assigned to them.

During the witchcraft crisis, however, all of that suddenly got turned upside down. Norton points out on page 10 that “during the crisis others tended to them, and magistrates and clergymen heeded their words.” Society itself was radically altered.

The chapters in the book are organized around a key topic. For example, chapter four is titled “The Dreadful Apparition of a Minister” and centers around accusations that the minister George Burroughs was appearing to the afflicted as an apparition in an attempt to get them to become witches and sign the Devil’s Book. The chapters’ organization makes it easy to go back and reference or re-read certain sections without having to go through the whole book to find a specific piece of information.

The two best parts about this book are how Norton presents all the facts in an easy-to-read manner as well as how she guides readers through the connections that she makes between people, places and events. Readers are never left wondering how she came up with a point or came to a conclusion. At 313 pages, this is a shorter history book and makes its points without the need for any filler.

This book is great for those interested in social cultural history, colonial New England/Atlantic World history or those interested in witchcraft history — specifically the Salem trials. It is extremely factual in nature, delving right into the small and intricate details, so I think it would appeal to undergraduates, graduate students and those researching the Salem witchcraft crisis.

If you’re interested in reading more books written by Norton, check out “Founding Mothers and Fathers” (1996) and her most recent story “1774: The Long Year of Revolution” (2020).